Working with matrices: addition, subtraction and multiplication

Last year, I had the chance to enrol in a mathematics degree by distance, which has been extremely helpful for filling in some gaps in my maths knowledge that I have coming from a behavioural sciences background. As I work my way through my degree, I’ll be posting about some of the things that I am learning that I think are relevant to the tools and techniques we work with in data science. In addition to helping me fully understand the material, hopefully it will be helpful for other people working in the field.

At the moment, I’m studying linear algebra, which (in addition to being a fascinating area of study in and of itself) has a lot of applications to the algorithms we work with in data science. To get started, I’d like to give a brief introduction to one of its basic units of analysis, the matrix.

What is a matrix?

No … we’re not going to be having that kind of conversation!

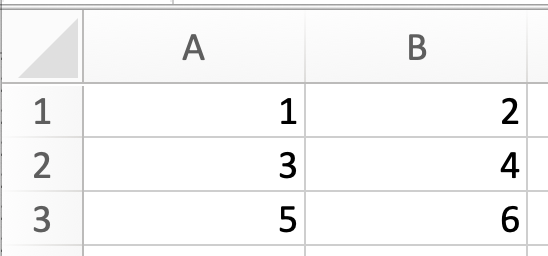

A matrix is simply an arrangement of symbols in a rectangle. The symbols can be anything, but from a mathematical point of view we’re mainly interested in those matrices that contain real numbers. You can think about a matrix like a table in Excel, where you have m rows and n columns, like so:

We can see this is an Excel spreadsheet with 3 rows and 2 columns, or a \(3 \times 2\) spreadsheet. If we were to represent these numbers in a matrix, we’d end up with:

a matrix called \(A\) with 3 rows and 2 columns, or a \(3 \times 2\) matrix.

We can represent this matrix in Python using a Numpy array. Notice that we’ve assigned each row of the matrix to a separate list, and then passed this list of lists as an argument to Numpy’s array function.

import numpy as np

A = np.array([[1, 2],[3, 4], [5, 6]])

A

array([[1, 2],

[3, 4],

[5, 6]])

Referring to matrix elements

Let’s go back to the Excel spreadsheet above. You’re probably used to the Excel notation of referring to elements in the spreadsheet using their column name and row number. For example, to get the element 2 in the spreadsheet above, you’d refer to cell B1, with the columns denoted by letters and the rows by numbers.

Similarly, we also refer to elements in matrices by their row and column positions.

In this case we’d reference the element 2 using \(a_{12}\). Unlike our Excel spreadsheet, however, we reference the row first and then the column. Also note that the convention when working with matrices is to refer to a matrix using a capital letter (\(A\)), and components of the matrix by a lowercase letter (\(a\)).

In Numpy, we can get elements from our array by using this row, column notation. However, because Python is zero-indexed, we need to subtract 1 from each of the row and column numbers, meaning \(a_{12}\) becomes (0, 1) in our Numpy array:

A.item((0, 1))

2

In addition, we can also refer to elements by their index in the matrix, treating each element as though it was part of a single list. In this case, 2 is at index 1 of the matrix:

A.item(1)

2

Matrix operations

There are a number of mathematical operations we can do with matrices. In this post, we’ll explore how to add and subtract matrices, how to multiply a matrix by a scalar, and how to multiply a matrix by another matrix. In the next post, I’ll explain matrix inversion (and when it is possible), and in the final post in this series we’ll cover powers of a matrix and matrix transposition.

Matrix addition and subtraction

Say we have two matrices, \(A\) and \(B\). If these matrices are the same size (that is, they both have \(m\) rows and \(n\) columns), we can add them together. We do this by adding each element in \(A\) with the equivalent element in \(B\) to get matrix \(C\), so that \(c_{11} = a_{11} + b_{11}, c_{12} = a_{12} + b_{12}\), up to \(c_{mn} = a_{mn} + b_{mn}\). It is therefore clear why the matrices must be the same size - otherwise the additional elements in the bigger matrix would have nothing to add or subtract in the smaller matrix!

So let’s define our new matrix \(B\), that we would like to add to \(A\):

Our new matrix \(C = A + B\) is then:

In Numpy, we can simply use the + operator, which correctly calculates this elementwise addition for each matrix.

B = np.array([[7, 8], [9, 10], [11, 12]])

C = A + B

C

array([[ 8, 10],

[12, 14],

[16, 18]])

This operation can also be extended to allow us to subtract a matrix from another matrix, where instead of adding each number in the two matrices, we would subtract one from the other. In Numpy we similarly use the - operator to perform this operation.

D = B - A

D

array([[6, 6],

[6, 6],

[6, 6]])

What happens if we try to add or subtract two matrices of different sizes? Let’s try adding \(A\) to a matrix made up of the first two rows of \(B\):

A + B[:2, :]

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ValueError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-25-b8ee924f9c9b> in <module>

----> 1 A + B[:2, :]

ValueError: operands could not be broadcast together with shapes (3,2) (2,2)

Numpy gives us a very helpful error message, reminding us that matrices must be the same shape in order to be added (or subtracted).

Multiplying a matrix by a scalar

We can also create a new matrix by multiplying a matrix by a real number (called a scalar in this context). Taking our original matrix \(A\) and a scalar (let’s say 2), we can create a new matrix \(E\) by multiplying every element of \(A\) by 2, like so:

In Numpy, similar to matrix addition and subtraction, we can just use the * operator to multiply each element by the scalar 2:

E = 2 * A

E

array([[ 2, 4],

[ 6, 8],

[10, 12]])

Matrix multiplication

So we’ve seen that matrices can be multiplied by scalars. Can we also multiply a matrix by another matrix? Just like with matrix addition and subtraction, this depends on the size of the two matrices. However, unlike addition and subtraction, the matrices don’t have to be the same size. Instead the number of columns in the first matrix must be the same as the number of rows in the second matrix. We’ll see why by doing an example.

Let’s say that we have a \(2 \times 4\) matrix, \(F\), and we want to multiply it by our matrix \(A\):

To get the first element of our new matrix \(AF\) (which we’ll call \(G\) to make it a bit neater), we use the following formula:

In other words, in order to get the first element of our new matrix \(G\), we multiply the first and second elements of the first row in \(A\) by the first and second elements of the first column in \(F\) respectively, and then add them. This operation is called taking the dot product of this row and this column. You can now see that this way of pairing of elements is why the number of columns in the first matrix must be the same as the number of rows in the second matrix.

Where do we go next? In order to get the next element \(g_{12}\) (that is, the second element of the first row), we take the elements of the first row of the first matrix and those of the second column of the second matrix and multiply them together like so:

Continuing this across all of the elements, we end up with:

And there we have it! We have ended up with a new \(3 \times 4\) matrix: that is, a matrix with the same number of rows as the first matrix and the same number of columns as the second matrix.

As hinted at in the name of operation that gets each element in our multiplication, the function to multiply two matrices in Numpy is called dot.

F = np.array([[10, 11, 12, 13], [14, 15, 16, 17]])

G = A.dot(F)

G

array([[ 38, 41, 44, 47],

[ 86, 93, 100, 107],

[134, 145, 156, 167]])

Alternatively, we can use the @ operator as a shortcut:

G = A @ F

G

array([[ 38, 41, 44, 47],

[ 86, 93, 100, 107],

[134, 145, 156, 167]])

What happens if we try to multiply two matrices that are not the right size? Let’s try multiplying \(A\) and \(F\) the other way around, meaning we’re trying to multiply a \(2 \times 4\) matrix by a \(3 \times 2\) matrix:

F.dot(A)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ValueError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-26-5cf9c7190280> in <module>

----> 1 F.dot(A)

ValueError: shapes (2,4) and (3,2) not aligned: 4 (dim 1) != 3 (dim 0)

As can be seen, Numpy throws a very useful error message which tells us that the number of columns in our first matrix (dim 1) is not the same as the number of rows in our second matrix (dim 0). This error message can be a lifesaver when you’re trying to do more complicated operations involving matrices!

This leads to one final point about matrix multiplication that might have already occurred to you. Matrix multiplication often only works in one direction, where it might be possible to multiply \(AF\) but not to multiply \(FA\). What’s more, even if it is possible to multiply the matrices both ways, the result will (usually) not be the same: \(AF \neq FA\). (In mathematical language, this means matrix multiplication is not commutative.)

Let’s try this out by multiplying \(A\) by a version of \(F\) where we drop the last column (giving us a \(3 \times 2\) matrix and a \(2 \times 3\) matrix). First, we multiply calculate \(AF_{\textrm{trimmed}}\):

A.dot(F[:, :3])

array([[ 38, 41, 44],

[ 86, 93, 100],

[134, 145, 156]])

Next, let’s try it the other way around, calculating \(F_{\textrm{trimmed}}A\):

F[:, :3].dot(A)

array([[103, 136],

[139, 184]])

We can see that not only are they not the same matrices, they are not even the same size, with \(AF_{\textrm{trimmed}}\) being a \(3 \times 3\) matrix, and \(F_{\textrm{trimmed}}A\) being a \(2 \times 2\) matrix.

I hope this was a useful introduction to what matrices are, and how to do some basic operations on them in Python. Next post we’ll move on to matrix inversion, which is a more advanced and interesting operation.