The pigeonhole principle

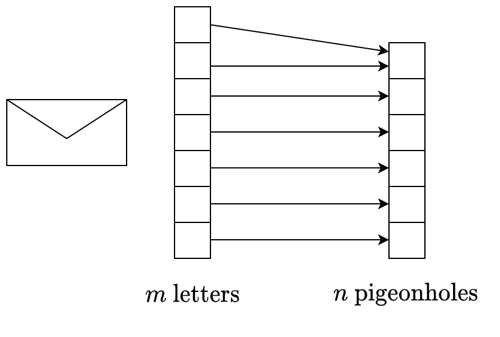

In this blog post, we’re going to talk about a very interesting application of functions called the piegonhole principle. The underlying idea is very simple. Imagine we have some quantity of letters \(m\), and a number of pigeonholes \(n\). If the number of letters is bigger than the number of pigeonholes, at least one of the pigeonholes will end up with more than one letter, as below. In other words, if the cardinality (the number of elements) of the set of letters is greater than the cardinality of the set of pigeonholes, or \(m > n\), then at least one of the pigeonholes will have more than one letter.

If you read my last blog post, you would recognise that this is an injective relationship (where every pigeonhole in our codomain maps to a letter in our domain), but it is not surjective (where there is a one-to-one relationship between every pigeonhole and letter). The underlying idea behind the pigeonhole principle is that we assume injectivity, although this doesn’t need to strictly hold for the principle to be true. We’ll discuss this more in the examples.

The pigeonhole principle allows us to make some interesting observations about situations that feel quite far removed from functions. Let’s have a look at a couple of examples.

Birthday months

Let’s imagine we have a random group of 13 people. Within this group, at least two of these people will have their birthdays in the same month.

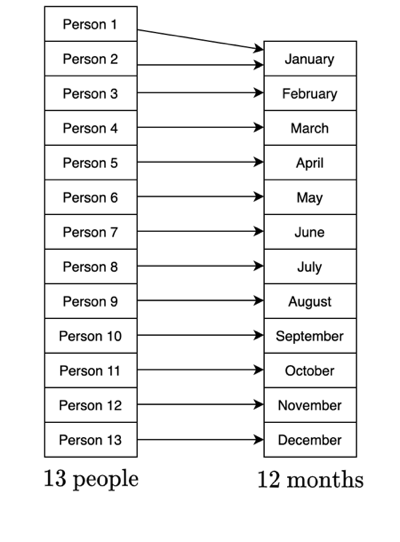

In order to solve this one, we need to imagine the group of 13 people as our domain, and the months of the year as our codomain. We assume injectivity, that is, that theoretically people could be mapped to every month of the year, as in the diagram below.

As we have 13 people but only 12 months, we cannot have a bijective relationship, as 13 > 12. Therefore at least 2 people have to be born in the same month. This is, of course, in the case that this function is injective for this group - if one or more birth months are not represented in this group of 13, we could have more than 2 people born in a given month. This is why we need to say at least 2 people will share a month.

Exam scores

Imagine we have 232 students enrolled in a mathematics course. The students must sit a final exam, with possible marks between 0 and 100. We’ll assume that the scores can only be integer values. At least 3 of these students will get the same exam mark.

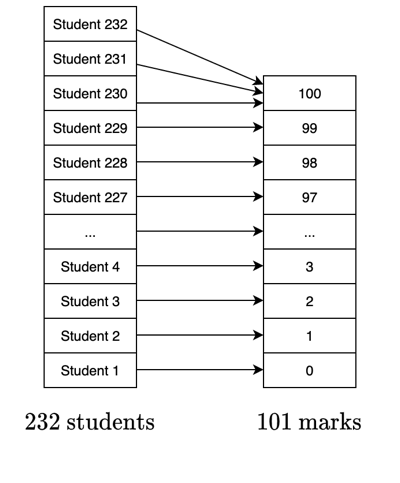

We think of the group of students as our domain with cardinality 232, and the marks as our codomain with cardinality 101, as below. Again, we assume injectivity, where every mark will be received by at least one student, as below.

As 232 divided by 101 has a quotient of 2, every mark will be received by at least 2 students. Then we have a remaining 31 students, who will need to be assigned marks that have already been received by at least 2 other students. Hence, at least one mark will be received by at least 3 students. More formally, since 232 > 2(101), there is some mark \(b\) such that 2 + 1 = 3 students will have \(f(a) = b\).

Friendship group

Here is a slightly more tricky example. Suppose that we have a set \(X\) of at least 2 people. Define the function \(f: X \rightarrow \{0, 1, 2, ..., n -1\}\) by \(f(x)\) being the number of people in \(X\) with whom \(x \in X\) is friends. For the purposes of this definition, no one can be their own friend, and we also assume that the friendship is reciprocal, that is, if \(x\) is friends with \(y\), then \(y\) is friends with \(x\). We need to 1) explain why it is not possible for there to be \(x, y \in X\) with \(f(x) = 0\) and \(f(y) = n - 1\), and 2) show that there at least two members of \(X\) who have the exact same number of friends in \(X\).

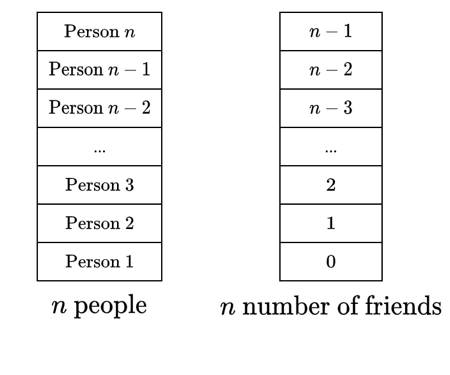

There is a lot going on in this question, so we’ll start again with a diagram defining \(X\) and \(\{0, 1, 2, ..., n - 1\}\).

Once you create these two sets, you can see something immediately. The cardinality of set \(X\) is \(n\), running from person 1 to person \(n\). However, the cardinality of \(\{0, 1, 2, ..., n -1\}\) is also \(n\), running from 0 to \(n - 1\). Hence, we currently have a bijection, so it would seem that the pigeonhole principle would not apply. However, we need to consider the first part of the question. Why would it be that we cannot have \(f(x) = 0\) and \(f(y) = n-1\) for two different people \(x, y\) in \(X\)?

Well, what this is saying is that we simultaneously have a person who has no friends (\(f(x) = 0\)) and a person who is friends with everyone (\(f(y) = n - 1\)), as remember, someone cannot be friends with themselves so the maximum number of friends is \(n - 1\). This cannot be true, as \(y\) would also be friends with \(x\) if they were friends with everyone. So we cannot map to both 0 and \(n - 1\) simultaneously. This means that the range of \(f\) is either \(Y = \{0, 1, 2, ..., n -2\}\) or \(Y = \{1, 2, ..., n -1\}\) (assuming injectivity), meaning that the cardinality is \(n - 1\). So now the cardinality of the group of people \(X\) is larger than the cardinality of the number of friends \(Y\), so as \(n > n - 1\), at least two people in the group will have exactly the same number of friends.