Have a think back to when GPT-4 came out in March 2023. One of the key things that OpenAI highlighted in their technical report was that this model was showing near-human performance, measured by how it scored on exams designed for humans. They reported finding that the model showed impressive performance on a range of professional and academic exams, including getting a score in the top 10% of test takers on a simulated bar exam. This led to a flurry of breathless headlines, like the one below, jumping to the conclusion that these models are at the level of some of the smartest people on the planet, and it will only be a matter of time before they're replacing professionals like doctors.

However, not everyone was convinced by these findings. For example, Horace He (one of the developers of PyTorch) wondered whether these seemingly remarkable results were simply because … the model had already seen the things it had been tested on (and the correct answers) during training. I mean, if you had access to the full answer sheet before you sat an exam, you'd get a pretty great result too, but it wouldn't mean you actually understood the material.

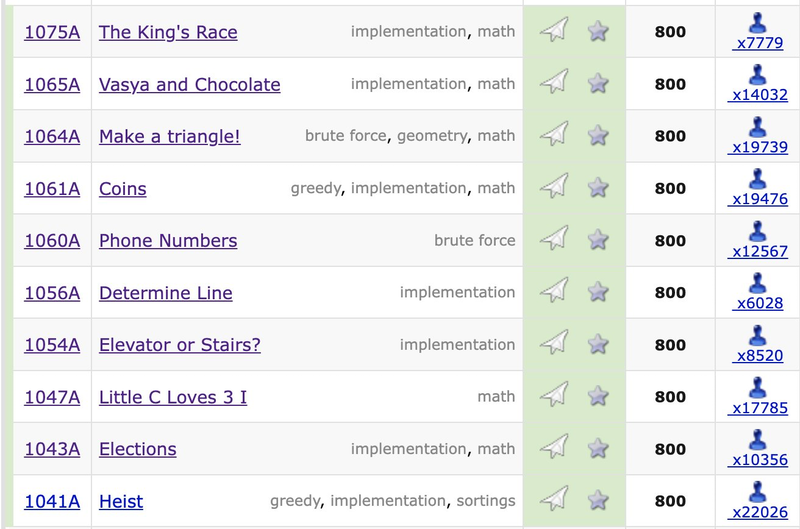

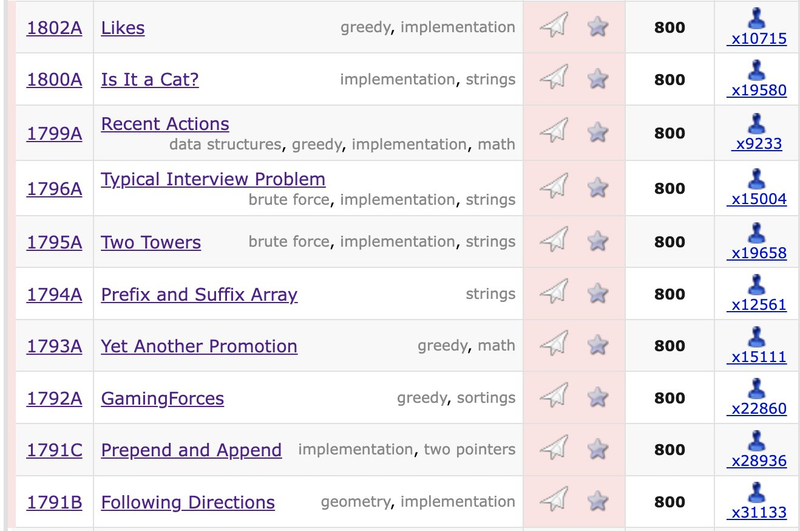

To assess this, He decided to look into GPT-4's performance on coding puzzles. He took puzzles from a website called CodeForces, which handily timestamps the dates that each puzzle is released onto the site. This meant that He was able to gather two sets of puzzles: those that were available when GPT-4 was being trained (and which therefore GPT-4 could have seen during training), and another set that were released after the model (and therefore could not have been in the model training set). He made sure that the two sets of puzzles were a similar level of difficulty.

When He gave GPT-4 the first set of puzzles, the one available during its training period, it got all of them right. So does this mean software developers are in danger of being replaced?

Well, not quite. He then passed in the second set of puzzles, the ones released after the model was trained, and this time, the model didn't get a single one correct . And remember, these puzzles were the same level of difficulty, so it certainly doesn't seem to be due to the second set of puzzles being more difficult. It's much more likely that GPT-4 was simply trained on the first set of CodeForces puzzles.

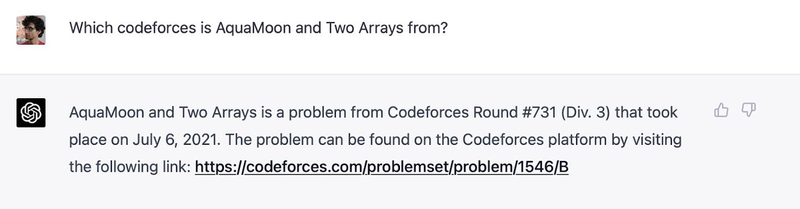

To confirm this, Sayash Kapoor prompted GPT-4 to tell him about a CodeForces puzzle that was available when it was trained. GPT-4 claimed familiarity with the puzzle - a response consistent with memorisation, though not definitive proof of inclusion in the training set. (We should be wary about trusting claims from LLMs definitively due to their tendency to hallucinate, something I explain further in my talk on LLM hallucinations and reliability.)

This is the phenomenon of data leakage in LLMs, and its a serious issue that compromises accurate LLM assessment.

What is data leakage in LLMs?

Data leakage in large language models occurs when evaluation data is included - directly or indirectly - in a model’s training data. This leads to inflated benchmark performance that reflects memorisation rather than genuine task understanding or generalisation. Data leakage really confuses the issue of what you're measuring: are you really assessing how good a model is at doing the task in question, or just how many of the answers they've already seen?

Data leakage in LLM benchmarks

One worrying example came from a 2024 paper by Simone Balloccu and his coauthors, who discovered that researchers assessing the capabilities of GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 were likely leaking items from LLM benchmarks into datasets that OpenAI could use for training future models.

They reviewed over 250 papers, and found that 90 had tested the GPT models in such a way that made data leakage likely, passing benchmark items to the models through the web interface, and having user agreements that allowed OpenAI to use the data for training further models. Overall, the authors of the reviewed papers leaked at least some items from 263 LLM assessments into this data, as shown in the table below (the columns represent the percentage of items per benchmark which were leaked). You can see the benchmarks affected represent the most common ways of assessing LLMs, from natural language generation, natural language inference, question answering, programming and math.

| Task type | < 5% | 5-50% | 50-95% | > 95% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI safety & ethics | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Creative NLG | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dialogue | 2 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| NLG evaluation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Machine Translation | 6 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Math | 0 | 1 | 0 | 8 |

| Natural language generation | 2 | 1 | 0 | 14 |

| Natural language inference | 6 | 2 | 0 | 15 |

| Language understanding | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Paraphrasing | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Politics | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Programming | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Psychology | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Question answering | 24 | 14 | 5 | 31 |

| Commonsense reasoning | 3 | 4 | 0 | 9 |

| Semantic similarity | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Sentiment analysis | 8 | 9 | 1 | 8 |

| Summarization | 5 | 6 | 1 | 1 |

| Text classification | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Text extraction | 2 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

Even assuming that model developers want to keep their training data free of contamination by benchmarks (which, more on that later in this article), this paper shows that doing so requires a constant and concerted effort, and depending on the public availability of benchmarks, may not really be feasible.

Are we running out of LLM training data?

The data leakage issue is complicated by the fact that data of sufficient quality to train and assess LLMs is a finite resource, and according to a study by Pablo Villalobos and colleagues, we may be coming close to running out of it.

Many model developers have increased the performance of their models by training them on increasingly larger datasets. This has led to an explosion in the training data size of models, from the 500 billion tokens used for GPT-3 in 2020, to the claims of training runs in the tens of trillions for Qwen3 and similar models in 2025. However, the total amount of human-generated public data suitable for training LLMs is estimated to be around 300 trillion tokens. If we continue training models in this way, we are likely to end up running out of useable text data in less than a decade, and as soon as 2027!

If every possible piece of public data has been consumed by these models, how can we assess them correctly? Moves have been made by the creators of the newest generation of benchmarks to keep them private, to make sure they are not consumed by LLMs in the voracious need for more and more data. But this doesn’t help general consumers of LLMs, who generally assess these models in a far less formal way, and who are likely to believe these models are getting better and better simply because they have memorised more and more data. As training data becomes saturated, the boundary between supposedly "unseen" evaluation data and training data becomes increasingly fragile.

Benchmark gaming and evaluation overfitting

So far, everything we've discussed is (likely) unintentional data leakage. However, there is also solid evidence that LLM creators are deliberately trying to fit their models to benchmarks, tuning the models prior to release to make them more likely to rank highly on leaderboards. This is a related phenomenon called evaluation overfitting, but results in largely the same issues of artificially high performance by these models.

One very notable case of this came out in the middle of 2025 which concerned the LM Arena, a popular way of comparing and ranking LLM performance. LLM creators who want to release their models onto the Arena are allowed to test out their model on a private dataset first, so they can get an idea of how it will perform. So naturally, you’d expect each company to only be using this dataset once: to test the model they had nominated for release.

However, some companies have been gaming this set up, testing multiple times and tuning the models to perform as well as possible on this dataset. Meta tested a whopping 27 variants of Llama-4 before release, gaming the testing protocol so they could release the model that would be most likely to rank well on the Arena. This inflates the model's performance upon release and gives it an artificially high ranking, which the model creators can take advantage of to tout how powerful their models are. However, as this is a semi-static benchmark, this performance will degrade over time to the actual ranking of the model.

Such practices further complicate the issue of data leakage, adding deliberate manipulation of testing methods to the already messy issues coming from contamination of the training sets.

And all of this has come about because - in our excitement to see LLMs as the "next step" in model training - we seem to have forgotten that they are still machine learning models, and still need to be trained and assessed according to machine learning best practices. Data leakage is a fundamental principle in ML, and by neglecting it when creating and using LLM assessments, we've really confused ourselves about the real performance of these models.

Key takeaways

- Many LLM benchmarks are affected by data leakage and training data contamination.

- Apparent improvements in LLM performance may reflect memorisation rather than true generalisation.

- Benchmark contamination makes it increasingly difficult to evaluate newer models fairly.

- Evaluation overfitting and benchmark gaming can artificially inflate leaderboard rankings.

- Reliable LLM evaluation requires stricter data controls, dynamic benchmarks, and better evaluation practices.

If you enjoyed this blog post, and you'd like to learn more about issues with LLM assessment, you can check out this keynote I gave on the topic. I'll also be writing further posts on this topic, so watch this space!